I started writing this essay in the Winter Garden nearly two weeks ago, the last time I felt my mind was truly clear. Ever since then, I have become increasingly addled by the process of trying to make meaning of that room where I sat for no more than an hour and a half. I was there to sneak an hour of reading in before rehearsal, and had just picked up a copy of W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz, after devouring his first book, Rings of Saturn.

The type of place a Chicago transplant would describe as a “hidden gem,” the Winter Garden is a tranquil spot. With only nine tables spaced out across the span of a city block, it is often impossible to find an open seat. Teal-colored walls and Grecian columns frame a marble floor and a glass ceiling with an arching steel frame floods the room with light. Even on cloudy days, the Winter Garden is strikingly bright. The space gives the appearance of a courtyard, and there are four olive trees in large planters. The leaves flutter from warm breaths of air, which are pumped from god-knows-where. The city feels far away, when in fact it is just below us, or next to us—as the Brown, Orange, and Pink lines skirt the third floor of this building. Maybe that is what is so unnerving about being in this room, besides that the air seems to be imbued with the color of its walls, and the chandeliers above look straight out of Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby. It is an odd space, halfway between spaceship and mausoleum, and is often filled with students, some of which sit on the floor up against the walls, studying, for in fact, the Winter Garden is the uppermost floor of the Harold Washington Library.

In Austerlitz, Sebald describes a train station which looks as if it would be a better suited as a zoo. I was struck by how the Winter Garden could be described similarly and of course, wondered what Sebald would think of such a place. Would he find this room absurd or amusing?

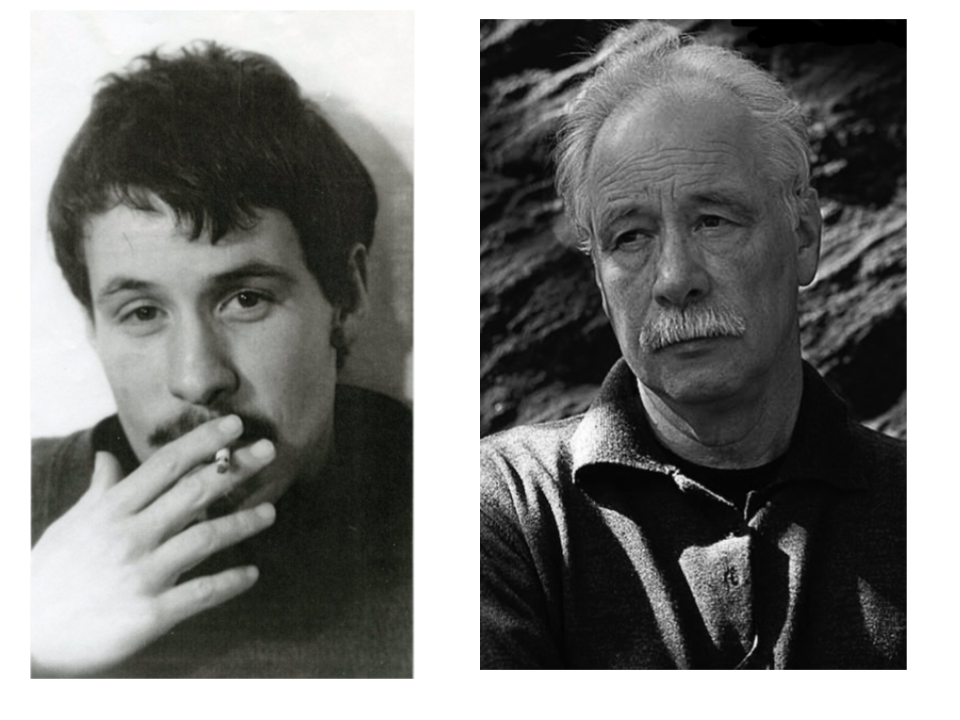

There are only a few photographs of W.G. Sebald when he is young. In his early twenties—dashing, thin, and mustachioed—he resembles the type of boys that currently sport beanies and sulk around Brooklyn (one of his favorite books as a student was The Catcher and the Rye.) Then there are the countless photos of him much older: a father and a retired literature professor. The same mustache makes him at fifty-four, look eccentric rather than austere. There is a loneliness in his gaze—or at least anyone who reads his texts would say there is, though such an observation is entirely baseless. These two renderings of him, and the fragmentation between them, are suggestive of themes that drive Sebald’s work. His characters experience betrayals of memory, history, and reality, leaving them with only subjectivity as a guide.

Born at the conclusion of World War II and raised in the perverse silence following the Holocaust, Sebald obsessed over that which went unspoken and undocumented. His narrators are often traveling, suspended from any real obligations. With their freedoms, they record architectural and personal histories. In Austerlitz, the narrator meets up with the title character at the newly constructed Brasserie Le Havane Bibliothèque Nationale, (National Library) in Paris. The Bibliothèque has a history of losing archives, whether to the squabbles of tyrannical monarchs in the 1600ds or the bombing of Paris during World War II. The narrator detests the new library, explaining:

“In order to reach the Grande Bibliotheque you have to travel through a desolate no-man's-land in one of those robot-driven Metro trains steered by a ghostly voice, or alternatively you have to catch a bus in the place Valhubert and then walk along the wind-swept riverbank towards the hideous, outsize building, the monumental dimensions of which were evidently inspired by the late President's wish to perpetuate his memory whilst, perhaps because it had to serve this purpose, it was so conceived that it is, as I realized on my first visit, said Austerlitz, both in its outer appearance and inner constitution unwelcoming if not inimical to human beings, and runs counter, on principle, one might say, to the requirements of any true reader.” (275-6)

Is the Winter Garden, with its frightening stillness, “inimical to human beings?” It’s hard to say. Through some research, I discovered that architect Stanley Tigerman proclaimed Chicago’s Harold Washington Library was deeply indebted to the design of the Bibliothèque Nationale. This connection, though tenuous, spurred in me a deep dive into the history of Harold Washington, for the sake of bringing me closer to this writer I will never meet.

One of the requirements for the Harold Washington build was that the new library must contain a plaza. At the Harold Washington, however, the ground floor, with its narrow hallways is like walking through a labyrinth—only to reach a rather underwhelming atrium. The architect, Thomas H. Beeby, declared that his plaza would live on the top floor: his Winter Garden. My friend half-jokingly asked if there was secret subliminal messaging in the fact that the atrium had so few tables. Hovering above the lower floors with an unnecessary exclusivity, was the hidden room an allegory of the underpinnings of racial and class hierarchies in America? After all, aren’t libraries supposed to be, well, welcoming? I admit I had not thought of it at first, but it makes sense. And of course, Beeby only sees fit to pay tribute to Western architecture. I admit there is something sinister about the utopia the room presents. It doesn’t apologize for anything. It doesn’t hold guilt the way some architecture does. So I think my friend is right. The utopian space would ultimately trouble Sebald—as it troubles me.

However, the history of the Harold Washington Library is not utopian, but utilitarian. There was, for a fifteen-year period encompassing the 60s, no real central Chicago library location. The accumulation of new collections began to outgrow the central Chicago library’s original premises at what is now the Cultural Center. With a great deal of diligence, the books were moved from building to building in the 70s and 80s, even to the top floor of a Michigan Avenue department store.

Harold Washington, Chicago’s first Black mayor and an avid reader, began the campaign for the construction of a new library, starting with a design contest. Ordinarily, a contest of this scope would attract hundreds of submissions—but because of the City’s requirements for the architect to attach themselves to contractors, the committee received only five entries from major firms. Most of the designs look extremely 80s, with long, tall panes of glass and an excess of rounded surfaces; many of them seem like they are trying to anticipate the future without any real sense of what it will look like. Of course, the committee chose the most conservative design—Thomas H. Beeby’s. This story seemed to convey the longstanding bureaucracy of Chicago, which thwarts attempts at innovation for the sake of getting things done. At its completion, Harold Washington was the second largest library in the world. The plot on which the Harold Washington Library was built was formerly a parking lot, and before that, a block of stores. I took particular delight in looking at a picture of the street view, where you can see it used to house a pornographic bookstore, servicing an entirely different group of readers.

Sebald also gets a kick out of ironies like this one. Though I confess, his observations are often more pointed and profound. Looking at monuments in Brussels he observes:

“At the most we gaze at [a vast edifice] in wonder, a kind of wonder which in itself is a form of dawning horror, for somehow we know by instinct that outsize buildings cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed from the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.” (19)

For Sebald, creation and destruction are bitterly intertwined. This quote makes me think of the vines growing over Chicago’s El tracks in the movie Divergent, or the limited series, Station Eleven. Chicago doesn’t get used for filming locations nearly as often as New York or Toronto, but when it does, the city is envisioned as an apocalyptic shell, the subtext being that Chicago could never survive the future; we’re irrationally beholden to the past.

Beeby, the Harold Washington architect, thought so. He envisioned a space of perfect homage to the existing architecture of Chicago, by collaging together the most recognizable elements of downtown buildings. Arched windows are reminiscent of Chicago’s municipalities, and red brick evokes the nearby Monadnock building. Stepping into Harold Washington, the space feels ancient, but the building was only completed in 1996. What appears from afar as a neoclassical wonder, is up close just a hodgepodge of references and signals that those of us who are not architects are too obtuse to understand.

The most impressive aspect of the library’s design is the crown of stone sculpture that adorns the roof. At its corners are giant feats of masonry: owls shrouded by Egyptian lotus leaves. I confess, I looked up lotus leaves on Google and could not see the resemblance. Supposedly, the leaves symbolize regrowth and rebirth. Lotuses (or water lilies) are impervious to water; their waxy surfaces allow drops to slide off the leaves back into the lake or river the plant lives on. It is even more curious that if the purpose of the sculptures were to communicate rebirth, why the stone creations were painted green to look like aged copper. How Sebaldian! It is as if any hope for regeneration can only be telegraphed from the past.

But maybe that’s true. After all, I have my own sort of prophet in Sebald. I ask him questions daily knowing he can’t respond. Sebald (or Max as he liked to be called) died in 2001, only a month after Austerlitz was published. His books suggest that the impact of trauma and histories only grow with the accumulation of time.

The same friend who asked me about the Winter Garden sent me a Tik Tok last week that described the Library of Babel, a concept extracted from a Jorge Luis Borges short story of the same name. The Library of Babel describes a library which contains an infinite combination of letters, and therefore every book, lyric, or text—even works still to be written. Unable to wade through the overabundance of information, the readers in the story ultimately find the library overwhelming and utterly useless. A programmer recently started a website to imitate a library of infinite sets based on the story. I narrowed the search to my name and pulled up a document. It looks a bit like this:

Staring at this wall of text, I felt finally convinced of the fallibility of libraries. I had begun to realize it in that confounding room, but it was only now that I understood. Libraries are places of contradiction. They are sites of both accumulation and loss, are both ghostly and earthly, organized and incoherent. And yet, somewhere in the Library of Babel are all the books Sebald never wrote. So I understand the instinct to make a building look older than it is. It is the same as when I use books written by dead guys as scaffolding for my entire life.

texts and sources I drew from:

https://libraryofbabel.info/

Speak, Silence: In Search of W.G. Sebald by Carole Angier

Austerlitz, Rings of Saturn, and The Emigrants by W.G. Sebald

The Library of Babel by Jorge Luis Borges

On Harold Washington:

https://press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/740668hwlc.html

http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1019.html

https://forgottenchicago.com/articles/building-new-25-years-of-the-harold-washington-library-center/

And now, for something completely different…

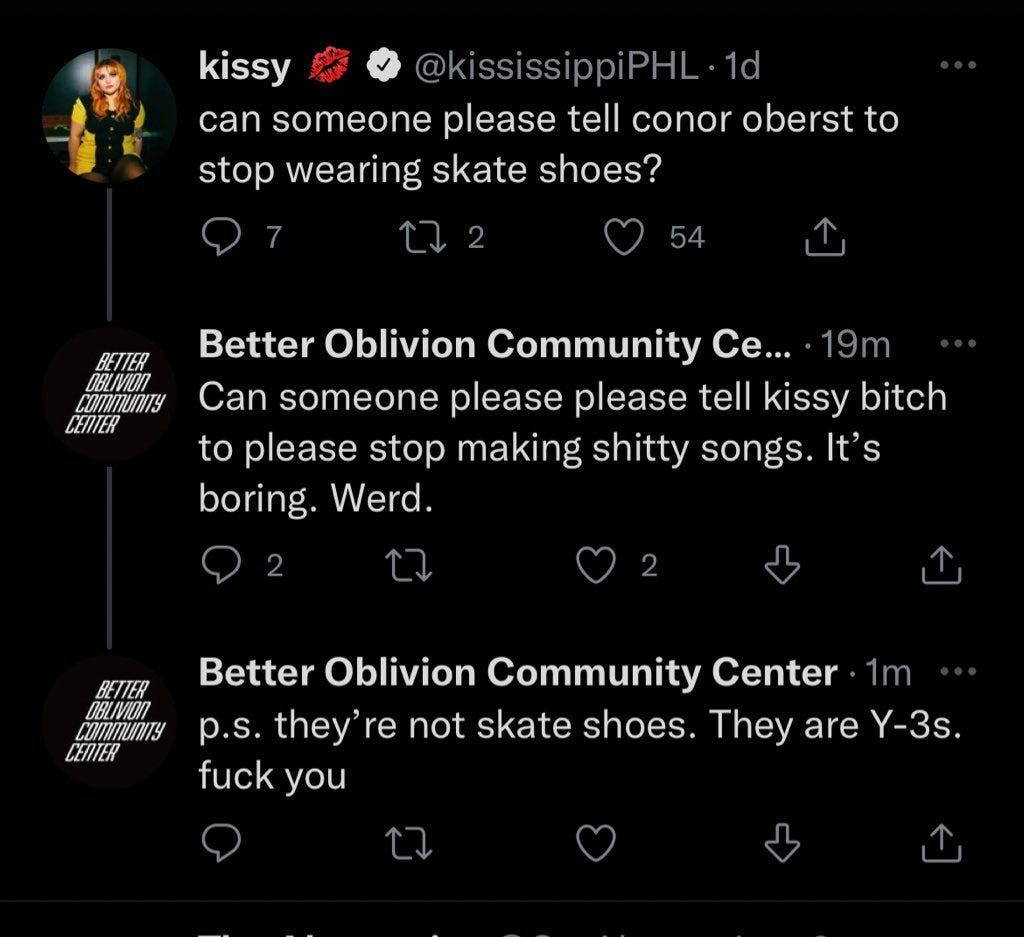

p.s. they’re not skate shoes. They are Y-3s. fuck you

Indie musician Conor Oberst tweeted for the first time in years. On April 11th 2022, the Better Oblivion Community Center account responded to a tweet that hadn’t even tagged him. Apparently this tweet from musician Kississippi was the last straw:

That final message has a poetry to it; it flies off the tongue. The inconsistency in use of capitalization and contractions….the periods placed perfectly to indicate an exorbitant amount of passive aggression….I’m horrified to report it is stuck in my head: p.s. they’re not skate shoes. They are Y-3s. fuck you

A work of art— thank you