Interviews with Vampires

Brad Pitt signed onto Interview with the Vampire with the understanding that it was going to be an arty, gay film that served as coming of age allegory. By the time he reached set, it was none of those things. He accepted the role based on the strength of the novel, which now seemed like an oversight. When he read the book, Pitt found sympathy for Louis, the depressed widower who was gifted a lust for life and immortality by the vampire Lestat. Pitt himself had transformed from ad man to actor, and had just spent his early twenties asking himself what he should do with all his newfound money and freedom. When Tom Cruise was offered the role of Lestat, Pitt became wary. Shortly after, the script’s references to the gay partnership between Lestat and Louis were quietly replaced in favor of the word “companion,” which, to Pitt, sounded gayer than if he and Cruise were wrapped up in sheets together.

The first few days of principal photography brought new problems. Despite the recent improvements to special effects, the best method for replicating vampiric skin was to suspend Pitt upside down from the ceiling. As the blood rushed to his head, the makeup artist, Michele, would faintly trace his protruding veins in blue, so as to make his skin appear translucent. Relentless night shoots meant Brad wasn’t getting a glimpse of sunlight, and he’d lost his Los Angeles tan by the time filming moved to London. Hanging upside down, bleary-eyed, and growing crankier each week, Pitt was beginning to find it hard to distinguish between himself and his character. He called David Geffen. Brad knew David wouldn’t hold it against him for asking.

“What would it cost me to leave this film?” He heard Geffen sigh.

“Forty million.”

Pitt laughed. It was a mirthless one, the kind that was shorthand for those in the industry—a laugh that stood for things unspoken but understood. He appreciated that David didn’t say anything stupid like “That’s showbiz.” He just let him complain.

Robert Pattinson similarly nearly walked away from a dizzying amount of money to leave Twilight—the most successful of vampire film of all time. “I think Twilight’s probably the hardest part I’ve done,” he has said without irony. On set, he was visited by his agents who complained that his moody approach to the character was going to lose him the job. They sent him rewritten versions of the script with “Edward smiles” in the parentheticals. The makeup used to whiten his teeth bothered Pattinson so much that he talked with his lips covering them. This way, the makeup crew would not notice any imperfections and reapply their strange pastes. The result was an accent strangely reminiscent of Gary Oldman’s Dracula, and mouth posture not unlike Nesfaratu.

Pattinson’s Twilight press tours are famous for his open disparagement of the films. On Jimmy Fallon, the host extolled on how sad it was for fans that the Twilight franchise was over. “For them!” Pattinson cried out as if unable to stop himself from saying it, then laughed jovially.

In his early interviews, Pattinson is bashful, if a bit mischievous. On Ellen, he hides behind a cardboard cut-out of Oprah to avoid the screams of women in the audience. His relationship to the media since the initial overwheming attention has progressed. Lately, he jadedly lies to interviewers, telling one that he invented a new spaghetti dish during COVID-19’s lockdown and subsequently nearly burns down his microwave with aluminum foil. His antics prod at the relentless performance that is a film’s press cycle.

Though the vampire metaphor maps cleanly onto issues of sex, queerness, disease, xenophobia, death, fame, religion—a neglected tie-in is between the vampire and performance. Bram Stoker was the acting manager of the still-standing Lyceum Theatre on the West End—and debuted the Dracula script before the novel. In Interview with the Vampire, Louis and his daughter visit a vampire theatre, where vampire elite re-enact their killings. Undead movies like Blade and Jennifer’s Body showcase artful killings–often on grand scale. Papparazzi photos of Robert Pattinson and Kirsten Stewart fed fans with unending content. In the music video for “Vampire,” Rodrigo is maimed by a stage light in front of a rapt audience.

After her wildly successful debut, Olivia Rodrigo thought the record label would trust her more. Knowing that” Vampire” was the lead single on her new album, the producers bothered Rodrigo about lyric changes. They asked if it made sense to refer to her ex as a “bloodsucker, fame fucker” since it wouldn’t be relatable to her average listener, who was neither famous or likely to be. She kept the lyric out of spite. After the COVID-19 pandemic, disease metaphors have become mutable; at-home and antigen tests track the virus’ departure from the body just as closely as its arrival. Indie musician Phoebe Bridgers sings “I am sick of the chase, but I’m hungry for blood” about loving her best friend, but turns the metaphor on its head in the song “Savior Complex” where she complains, “You’re a vampire, you want blood and I promised.” Vampirism is no longer an irreversible state of monsterdom, but an indictment of transitory power dynamics. Is it misrepresentative to mention former vampires Pitt, Cruise, and Pattinson have all been credibly accused of varying degrees of monstrosity? The new media landscape requires moviegoers to hold monstrosity and humanity in the same mental picture.

Anne Rice, the author of Interview with the Vampire, never wanted Tom Cruise for the role. She had already—she felt—made a concession with Brad Pitt, who was too classically handsome and stodgily built. But the producers were clearly out of their minds. Lestalt was for a seductive, Oscar Wilde type, not an action star. She begged them to at least swap the roles. Brad, with his arched eyebrows and girlish hair might be able to pull off the muddled sexuality of the evil obsessive. What Anne couldn’t say, but what was the subtext of all her complaints was that Lestalt was more than anything, queer.

It was not until she saw the film, and her hardened frustrations gave way after the long timeline of moviemaking had passed, that she relented that Cruise’s performance was admirable. The gaunt makeup had helped, even if he wasn’t a believable blonde. That soulless stare…one couldn’t help but be reminded of the rumors about his indoctrination into the Church of Scientology. There would always be something untrustworthy about him, but the man could act. Who other than Cruise could conjure up a soul for something already dead? Then, lingering in the lobby post-premiere, she realized the truth. Famed actors were gingerly walking around in their gowns, taking care with their martini glasses. The casting didn’t matter; they just required stars. In today’s day and age, she realized, those who have made it onto the silver screen are the vampire’s closest kin; they know most intimately what it’s like to be immortal.

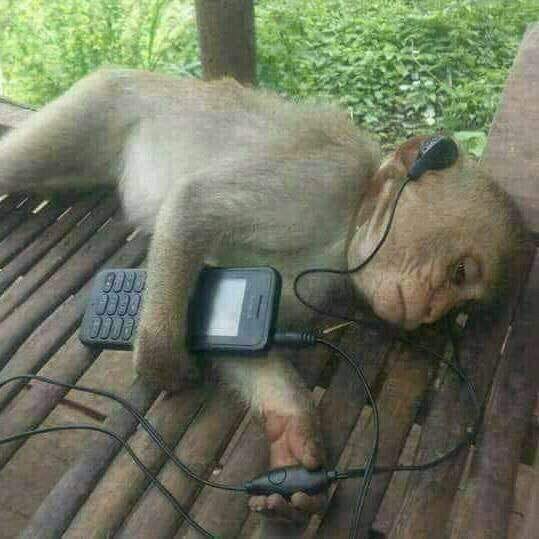

Monkey Unemployed

This is the part of the blog where I share what I’m listening to lately. Since I’m working on job/school applications, I’ve been playing a lot of instrumental. Namely, Johnny Greenwood’s Phantom Thread score. It’s truly the only thing that keeps me focused without feeling like I’m just passively listening!

Thank you as always for reading. :)